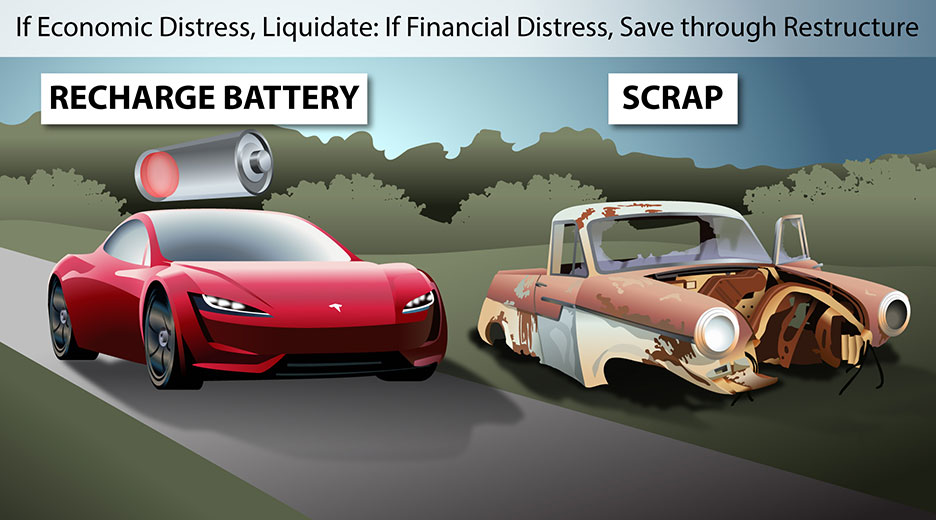

If Economic Distress, Liquidate. If Financial Distress, Save through Restructure.

Businesses can struggle or fail in different ways. Consider an unprofitable transport business that hasn’t been able to put up rates in 20 years due to stiff competition. Or, consider the same type of business, where its unprofitability is caused by the inability to pay debts entered into by prior directors.

In article:

Sometimes the first situation is referred to as ‘economic distress’, and contrasted with the second situation, which is referred to as ‘financial distress’. In either case, the owners/directors of the business have an important decision to make; liquidate or restructure? Or, to put it another way, is the business still viable, or is it fundamentally wrongly ‘wired’?

In this article, we examine the distinction between economic and financial distress, and look at how it impacts on the decision of a business to liquidate or restructure.

What is the difference between economic and financial distress?

The technical difference between financial and economic distress has been described in the following way:

- Financial distress occurs where the business is without fundamental problems, but is highly leveraged and having difficulty paying its debts. On this definition, distress is tied to capital structure.

- Economic distress also occurs when the business is unable to pay its debts, but occurs where the business is not competitive and has fundamental problems with its business model. Another way of putting this is that a business is under economic distress where that business is not viable.

According to research in the US, the Chapter 11 process (a debtor-in-possession restructuring mechanism) has been useful for reviving financially distressed firms, but not those under economic distress. In the latter case, it is more likely for the business to go bankrupt and simply have its assets realised and distributed to creditors. This coheres with the theoretical ideal that ‘debtor-in-possession’ restructuring is useful only to preserve firms that are still viable.

This conclusion also aligns with business valuation theory. When valuing a business, it is common to focus on EBITDA – earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation — rather than current net profit, i.e. the cost of financing is excluded from calculations. This is for several reasons:

- Including financing costs would give an inaccurate picture of future earnings. For example, a tech startup will often have significant debt financing early on to fund research and development. This cost will reduce/disappear once the company has a viable product.

- It can provide a better basis for comparison between firms (who will have different financing costs).

Perhaps most fundamentally, financing costs can be altered; debts can be forgiven, and re-financing can occur. This is not true with many of the financial pressures that apply to economically distressed firms.

Which options in Australia are well-suited to a financially distressed business?

In recent doctoral research, the University of Sydney’s Professor Jason Harris analysed the success of Australian insolvency mechanisms and concluded that corporate rescue (i.e. restructuring) should be focused on by businesses in financial distress, not economic distress.

So, what options might be considered for a financially distressed business? Consider:

- Voluntary administration. In theory, this option is available. This means an independent insolvency practitioner is appointed to take over the company and work towards a deal with creditors (a ‘Deed of Company Arrangement’ or ‘DOCA’). In reality, it is extremely rare for a voluntary administration in Australia to lead to a successful DOCA (for more information, see our Complete Guide to Voluntary Administration).

- Small business debt restructuring. This is a new insolvency procedure available for small businesses (where debts are less than $1 million). It is too early to say how successful this option might be. As a ‘debtor in possession’ model, the directors of the distressed company could approach creditors with a view to debt forgiveness.

- Pre-pack with liquidation or voluntary administration. In a ‘pre-pack’ (short for ‘pre-packaged insolvency arrangement’), the directors of the distressed business arrange for the assets of the business to be sold (at fair market value) to a new corporate entity. In many cases, those directors go on to oversee the new entity. A pre-pack will require approval from a liquidator or voluntary administrator. This can be a useful way of preserving the business as a going concern where distress relates to financing. Read more about this process here.

Which options in Australia may be suited to an economically distressed business?

Where a business is under economic distress, by definition, questions exist as to whether the business is viable. This means that the core goal of any insolvency procedure should be to maximise returns for creditors, rather than preserve the business itself. Consider how the available options measure against this goal:

- Receivership. In receivership, an insolvency practitioner is appointed by a secured creditor to secure assets and get maximum return on any asset sale. The downside of this approach is that unsecured creditors have no entitlement through the receivership. Furthermore, the high fees of receivers are paid by the distressed company — this further depletes any remaining asset pool that might eventually be available for distribution to unsecured creditors.

- Simplified liquidation. This new liquidation process is available for small businesses only (debts of less than $1 million). It is less likely to deplete asset value for unsecured creditors than a standard liquidation, as liquidation happens more quickly and with fewer expensive formalities (such as reports to creditors and ‘committees of inspection’).

- Voluntary administration. This process is even more ill-suited to an economically distressed business, than it is to a financially distressed business. As the business is unlikely to survive, a liquidation is inevitable with the asset pool likely to be further depleted by the voluntary administration (though note below, sometimes voluntary administration is inevitable – such as in the case of large corporates).

- Informal workouts. An informal workout with creditors — getting creditors to agree on a compromise of their debt — may be optimal, but it is extremely difficult to get creditors ‘out of the money’ to agree not to pursue action.

- Standard liquidation. This option can be difficult for larger businesses as directors cannot appoint a liquidator by resolution: They must a convene a meeting of members/shareholders, 75% of whom must vote in favour of the liquidation. Therefore, it is inevitable in many cases that the directors will need to first appoint a voluntary administrator.

- Becoming a zombie company. A zombie company continues to struggle on despite its fundamental lack of viability. Eventually, it will be wound up involuntarily, and/or owners will stop contributing funding.

Conclusion

For any struggling company, a crucial question for directors should be ‘is my business in financial distress, or is it in economic distress?’. This means taking a hard look at the profit and loss of the business. What service or product lines are actually profitable? And what does an acceptable profit look like? If income is flat, and expenses are rising, a realistic assessment needs to be made.

Once the company has determined that it is under financial or economic distress, it needs to consider which insolvency or restructuring mechanism is appropriate. Where the business is economically distressed, it is likely that restructuring won’t work and, one way or another, the business needs to be wound up.