What are the duties of insolvency practitioners in Australia?

Corporate insolvency practitioners are important gatekeepers in the economy. In Australia, there is a paradox that the system is designed to try to stop the insolvency practitioner from giving meaningful pre-insolvency advice to insolvent businesses. This is a pity because insolvency practitioners are well placed to give pre-insolvency advice.

In article:

- The role of the insolvency practitioner

- Insolvency practitioners have no duty to directors

- Duties of insolvency practitioners as an officer of the company

- Duties of insolvency practitioners as a fiduciary

- Duties of insolvency practitioners via statutory role

- Professional duties of insolvency practitioners

- Duties of insolvency practitioners via ASIC undertakings

- How can action be taken for a breach of duty?

In some cases, insolvency practitioners have been known to promise business rescue to directors, while in full knowledge that a voluntary administration is likely to fail. As a bulwark against this behaviour, insolvency practitioners in Australia have a range of legal and professional duties. However, there is a conflict between their duty of independence and their duties to creditors.

Here we take a look at the key duties of insolvency practitioners and what can be done where there has been a breach of duty.

The role of the insolvency practitioner

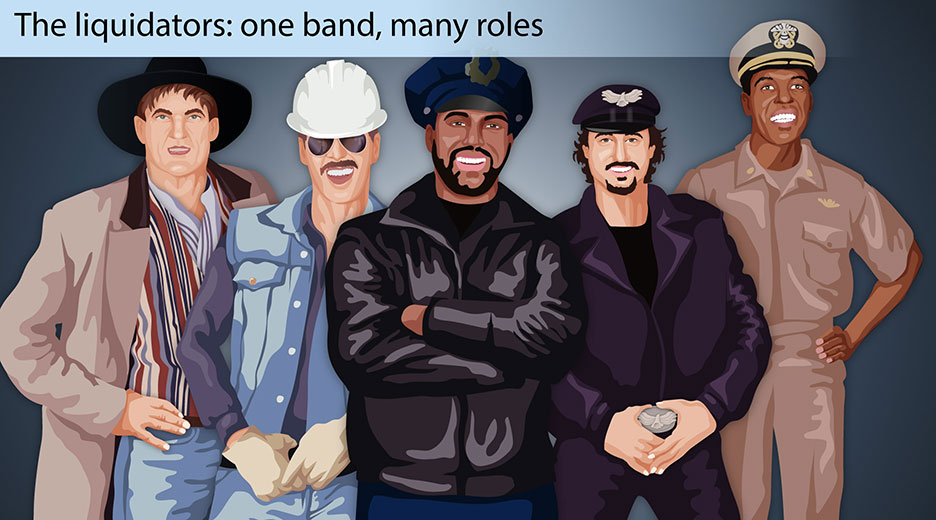

Insolvency practitioners may operate in either personal bankruptcy (as a bankruptcy trustee) or in corporate insolvency (as a liquidator, voluntary administrator, receiver or small business restructuring practitioner).

The role is complex, with the insolvency practitioner having oversight and control over the insolvency process. It is a powerful role. In the words of Michael Murray and Jason Harris:

“These authorised individuals often exercise quasi-judicial powers which can include closing down a business, sacking employees, restraining creditors from seizing assets and pursuing litigation against those involved in contravention of the law (such as breaches of directors’ duties and voidable transactions)” (Harris, J., and Murray, M. (2018). Keay’s Insolvency,10th ed, Thomson Reuters, p38).

Elizabeth Nosworthy and Christopher Symes observed that the complex role of the insolvency practitioners means that law has treated them as a ‘hybrid composite’, capturing the duties of an ‘agent, fiduciary and officer’.

Given the substantial powers and rights afforded to insolvency practitioners, it is important that they have duties under the law which are strictly enforced. Here we look at the duties of insolvency practitioners with a focus on the statutory obligations, fiduciary obligations and professional obligations.

Insolvency practitioners have no duty to directors

Before looking at the duties of insolvency practitioners, it is worth observing an important group that insolvency practitioners do not have duties towards — directors.

In most cases, insolvency practitioners are appointed by a resolution of the company directors, and the directors choose the insolvency practitioner they wish to be appointed. Therefore, prima facie, directors may expect liquidators to ‘work for them’.

But that’s not how it works. Insolvency practitioners have no duty to directors, as such a duty would be a conflict of interest. A core role of the insolvency practitioner is to investigate the past conduct of directors and pursue directors to recover funds (eg. through unfair preferences and other voidable transactions) and/or report misbehaviour to ASIC.

In fact, the rules that apply to most insolvency practitioners specify that prior to appointment, insolvency practitioners are not allowed to provide substantive advice to directors, only general options (see more on this below). In our experience, this is often not followed in practice (though there is a dearth of empirical research on the point).

Duties of insolvency practitioners as an officer of the company

On appointment, the liquidator usually becomes an officer of the corporation (note, there are some exceptions – see Owen, in the matter of RiverCity Motorway Pty Limited (Administrators Appointed) (Receivers and Managers Appointed) [2014] FCA 1008).

This is because section 9, paragraph (f) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) defines “officer” as including “a liquidator of the corporation”. This means that the liquidator has:

- A duty of care and diligence in carrying out their powers and duties (section 180);

- A duty to act in good faith in the best interests of the company, and for a proper purpose (section 181) – where this duty is breached with recklessness or intent, it is a criminal offence (section 184);

- A duty not to improperly use their position to gain an advantage for themselves or someone else, or to cause detriment to the corporation (section 182); and

- A duty not to improperly use information to their own advantage, or to the detriment of the company (section 183).

Duties of insolvency practitioners as a fiduciary

A fiduciary relationship is a special kind of legal relationship where one party (the fiduciary) owes the other party (the principal), the highest duty of care. A liquidator is a fiduciary, and in this context has a:

- A duty of independence, including to be perceived to be independent;

- A duty to avoid conflicts of interest; and

- A duty not to improperly profit from the arrangement.

For an extensive discussion of the liquidator’s fiduciary duty of independence, see The Ultimate Guide to Liquidation Part 3: Responding to Liquidation.

However, it is worth noting that there are no fiduciary duties owed between the insolvency practitioner and the company director. This is unlike, for example, lawyers and stockbrokers who are fiduciaries to the people they advise, with this being set out in a contract between the two parties. This is a pity in our view because company directors usually rely on the advice provided by insolvency practitioners (to some extent) before the appointment commences. That advice could relate to the necessity of an appointment, the type of insolvency appointment or even just the timing of the appointment.

Duties of insolvency practitioners via statutory role

In addition to their duties as officers, liquidators (or voluntary administrators, or small business restructuring practitioners as the case may be) have duties specific to their role. These duties for liquidators are set out in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), they include:

- The duty to collect and protect the company’s assets;

- The duty to investigate and report to creditors on the company’s affairs;

- The duty to inquire into why the company failed (including reporting any offences to ASIC);

- The duty to distribute the proceeds of the liquidation; and

- The duty to keep records.

For more information see Insolvency for investors and shareholders.

Professional duties of insolvency practitioners

Besides legal duties, insolvency practitioners also usually have professionalduties applied by various professional bodies.

Almost all insolvency practitioners in Australia are qualified accountants. This is because it is difficult (though not impossible) to otherwise meet the current experience requirements set by ASIC.

Professional accountants in Australia must abide by the requirements of the Accounting Professional and Ethical Standards Board (APESB), and specifically its Code of Ethics. This includes duties of independence, to avoid conflicts of interest and a duty to act with sufficient expertise.

Insolvency practitioners are also often members of the Australian Restructuring, Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA), which means that all members are subject to their Code of Professional Practice.

This provides strict guidance, especially around pre-appointment advice to directors, including requirements:

- not to give any assurance about the outcome of the insolvency;

- to explain that information provided by the director may be used during the administration; and

- to explain that the directors will have obligations to, and be subject to the claims of, the insolvency practitioner.

There is a broader philosophical question around whether insolvency practitioners should have any professional duties, as it is not clear that they constitute a profession at all. There seems to be little collegiality across the industry, nor an underlying ‘ethical core’ for insolvency practitioners, such as those that govern lawyers or doctors.

The public perception of the industry is certainly fairly dodgy. Just consider Senator John Wacka Williams’ expression of concern about “wrongdoings, possibly the abuse of power and even corruption in some sectors of the industry”.

For an in depth consideration of the ‘professionalism’ question see Michael Murray’s Does insolvency practice constitute a profession?.

Duties of insolvency practitioners via ASIC undertakings

In addition to duties that apply to all insolvency practitioners, some insolvency practitioners may have duties applied to them by voluntary undertaking. These are set and enforced by ASIC as part of its regulatory role. These might include:

- A duty not to accept any new insolvency appointments;

- A duty to undertake specified training; and

- A duty to have work independently reviewed.

How can action be taken for a breach of duty?

If insolvency practitioners do breach their duties, what can be done about it? There are several options:

- Regulator action. ASIC is the key regulator. They can make directions to liquidators, require additional training and ultimately apply for cancellation of registration. In recent years ASIC has tightened up the registration process and is focused on increasing the professionalisation of the industry.

- Voluntary court action. The Court can take action of its own volition to remove a liquidator for breach of duty (see section 536 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)).

- Individual complaint. Any individual can make a complaint to the court about the conduct of a liquidator (ie. any creditor/the commissioner of taxation can make a complaint). See for example, Commissioner of Taxation v Iannuzzi (No 2) [2019] FCA 1818. The expense of an individual (non-ATO) creditor taking such a case means that this rarely occurs (we are aware of no cases).

- Cause of action in tort or equity. Where there is breach of legal duty, and a creditor has suffered damages, they could bring an action such as breach of statutory duty, breach of trust or breach of fiduciary duty, depending on the circumstances. Note, that because directors and liquidators control the books, it would be difficult for creditors to acquire proof. There are few cases (if any) where a creditor (other than the ATO) has commenced legal action against an insolvency practitioner for breach of a duty (other than to replace the appointee).

One might say that the best action that could be taken is realism — to understand that an insolvency appointment is not a guaranteed corporate rescue, it is a necessary step to deal with an insolvent company and to avoid an insolvent trading allegation. Therefore, for a disappointed creditor or director, any action for breach of duty will be of limited effect.

From a director’s perspective, the key lesson is to seek out independent professional advice before a winding up may be necessary. Ideally this advice should be from an advisor who owes the director a fiduciary duty and can give good faith advice about potential outcomes. Our experience is that directors who have been through a voluntary administration in the past are the most likely to engage our firm before considering going through the process again.