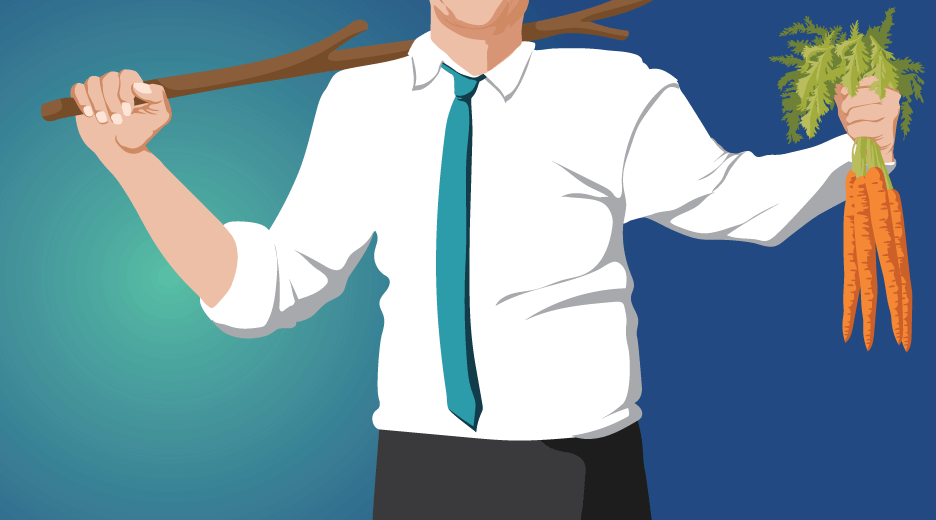

What needs to be changed in Australian insolvency law: More carrots and less stick for directors

The existing policy-settings for insolvency law need some serious alteration. The threat of ‘terminators’ means too often directors are subject to the ‘stick’ of the law. A better system would provide positive incentives, ‘carrots’, for directors and their accountants and lawyers, to turn companies around.

In article:

Summary

- Australian insolvency law, as it currently stands, incentivises the termination of businesses upon insolvency;

- An alternative model would incentivise the genuine ‘turnaround’ or transformation of a business so that it would continue as a going concern;

- Policymakers should consider whether Australia needs to adopt ‘debtor-in-possession’ mechanisms or, alternatively, make it easier to carry out ‘pre-pack insolvency arrangements’. This would positively incentivise the restructuring and survival of a business.

Australian insolvency law, as currently structured, is the worst-case scenario. It’s bad for individual businesses (especially small and medium-sized enterprises, or ‘SMEs’), creditors and the economy as a whole. Directors have no incentive to seek help before its too late, insolvency professionals have no incentive to turn a business around and upon liquidation, creditors end up with cents on the dollar. In this article we explore the prevailing insolvency industry culture and policy-settings in Australia, look at how other countries do things differently and, finally, suggest how policymakers might begin to turn things around.

Insolvency Professionals are Terminators

In Australia, very few businesses survive an external administration process (such as the appointment of a Voluntary Administrator or a Liquidator). Statistics show that, once the insolvency professional has done their job, the business is usually wound up. On 2019 data, we estimate that less than one per cent of businesses that enter into a Voluntary Administration process is successfully restructured and continue as a going concern. ‘Termination’ professional may be a more apt name than ‘turnaround’ professional. This tendency for businesses to be wound up following an administration process is absorbed by broader society and has led to a stigma surrounding the process. Once a business has entered into the process it is often viewed as ‘tainted’ and customers and creditors are reluctant to trust that business again. It is certainly unforeseeable in Australia that a business person who has gone through insolvency would be elected to high office.

So why does this happen? Why do insolvency professionals terminate, rather than transform, businesses? Insolvency professionals can be quick to deny responsibility: at the time of their appointment, it may be too late to turn the business around. Perhaps this suggests that insolvency culture in Australia is a vicious cycle? Perhaps businesses fear the stigma of administration processes and therefore fail to seek intervention early enough, which in turn leads to the vast majority of companies being wound up?

It cannot be denied, however, that existing insolvency laws and policy-settings incentivise the terminators. Insolvency practitioners are able to develop relatively standardised (and cost-effective) winding up processes, with the actual work carried out largely by junior accountants. Then, the priority rules in section 556 of the Corporations Act 2001 kick in to ensure that the terminators get their cut before general creditors. There is zero incentive for insolvency professionals to train their staff in a completely separate, and bespoke process of turnaround, which has no clear prospect of greater profits for them.

The terminators also benefit from the opacity of winding-up process. There is no public record of what occurs during the insolvency process, what insolvency professionals have done to try and turn around a business and what they were paid for their services. This compounds the apparent vicious cycle of insolvency: As there is little public awareness of their fee-setting and outcomes achieved (usually poor ones, from the perspective of creditors), they can continue to command high fees.

Policy-settings don’t only incentivise the terminators: they incentivise directors to appoint the terminators. Directors are often concerned about legal and compliance risks if they attempt to restructure when in financial difficulty. This is due to the prohibition on insolvent trading under section 588G of the Corporations Act 2001 and a general regulator spotlight on ‘phoenix’ activity. From a directors perspective, these risks might be thought best minimised by simply winding up the business. This applies particularly with public company non-executive directors who do not have ‘skin’ in the game and no financial incentive to take any risk that would personally expose them to litigation.

Recent policy developments, including the new ‘safe harbour’ provisions and the Insolvency Law Reform Act, do provide protection for a director restructure under certain circumstances. However, directors need to be very careful that they follow the requirements of section 588GA closely (for example, continuing to pay employee entitlements and filing tax returns as they fall due) or they will not be able to use its protection.

Insolvency Practitioners should be Transformers

The economic rule which underlies any sensible insolvency policy-setting is simple: If the surplus of going concern value is higher than the surplus of Liquidation value, save the business. That is, transform a struggling business into a viable business. But Australian insolvency law, in general, works against this rule. Arguably, insolvency policy-settings in Australia are designed around what might be sensible for large corporations and corporate groups. They have the financial resources (whether via cross-company guarantees from the corporate group or bank loans) to support a struggling venture. This means appointing a voluntary administrator is truly a last resort.

But this is not the case for SMEs and start-ups in Australia. With small capital reserves and limited access to loans, a small adverse event (such as one major client refusing to pay their invoice) can up-end an SME. On Liquidation, their biggest creditor is usually the Australian Tax Office. If the biggest loss is to the taxpayer anyway, it raises the question of whether taxpayers would be better served by that business surviving. In addition, the personal investment that owners and families usually have in their own business can make the failure especially devastating.

When current Voluntary Administration laws Australia were set as a result of the ‘Harmer Report’ in the 1980s, it was envisaged that viable companies would be saved by Voluntary Administration: As stated above, this hasn’t happened. Voluntary Administrations are very likely to end up in the winding up of the company eventually. This compounds the poor returns for creditors at the eventual winding up: the potential pool for creditors is further depleted by the Voluntary Administrator’s fees and expenses.

This approach, that policy-settings need to focus on transformation, not termination, aligns with Professor Sir Roy Goode’s ‘gold standard’ four objectives for insolvency law:

- Rescue the company where practicable;

- If the company cannot be saved, maximise returns for creditors;

- Establish a fair system for ranking claims amongst competing creditors;

- Constitute a mechanism for identifying the causes of failure.

What remains to be determined is the right way of implementing these general principles for insolvency law.

Going forward: More Carrot less Stick

The existing policy-settings for insolvency law need some serious alteration. The threat of ‘terminators’ means too often directors are subject to the ‘stick’ of the law. A better system would provide positive incentives, ‘carrots’, for directors and their accountants and lawyers, to turn companies around.

This would be best achieved by insolvency policy that emphasises early intervention and distinguishes between the different pressures on SMEs and large corporations or corporate groups. One possibility is to introduce robust ‘debtor-in-possession’ mechanisms, such as the United States Bankruptcy Code’s Chapter 11. As with Voluntary Administration, this is an alternative to Liquidation. However, unlike a Voluntary Administration, an independent insolvency professional does not take control. Rather, Chapter 11 permits the management to remain in possession of the company and work on a plan for reorganisation, under the supervision of a specialist court. While going through this process, there is an automatic stay on creditor’s pursuing their debts or litigation.

In May 2017, Singapore introduced a new insolvency regime that incorporates elements of the Chapter 11 process. As with Chapter 11, the new provisions of the Companies Act establish a moratorium on proceedings against the debtor company and a super-priority for rescue financing. Singapore, unlike Australia, is positioning itself to be the leading financial centre in Asia. Australia has no serious plans, however, to have the London or New York of Asia.

In Australia, an alternative reform may be to change existing laws for SMEs to support them using ‘pre-pack insolvency arrangements’ as a restructuring method. A pre-pack insolvency arrangement is an instrument for rescuing an insolvent business through an asset transfer completed either before or after the formal appointment of an Insolvency Practitioner. Presently it is not universally accepted as an appropriate restructuring method in Australia.

It is an alternative to using Voluntary Administration for rescuing an insolvent business from a Liquidation. When carried out correctly this does not constitute illegal ‘phoenix’ activity as any business assets are only transferred at fair market value and the process is supervised by an Insolvency Practitioner. ‘Pre-packs’ have now been adopted as standard practice for SMEs in the United Kingdom but Insolvency Practitioners in Australia aren’t trusted with these types of assignments due to restrictive conflict of interest law.

This is already a useful option for businesses to consider under existing law, however, directors and their professional advisers are understandably cautious. They are aware that any pre-pack will be scrutinised in any subsequent Voluntary Administration or Liquidation. In light of this, policymakers may need to consider enhanced protections for directors who pursue this option.

For more information on pre-pack arrangements please see our white paper on the topic, What you need to know before you pre-pack (to avoid phoenix activity).